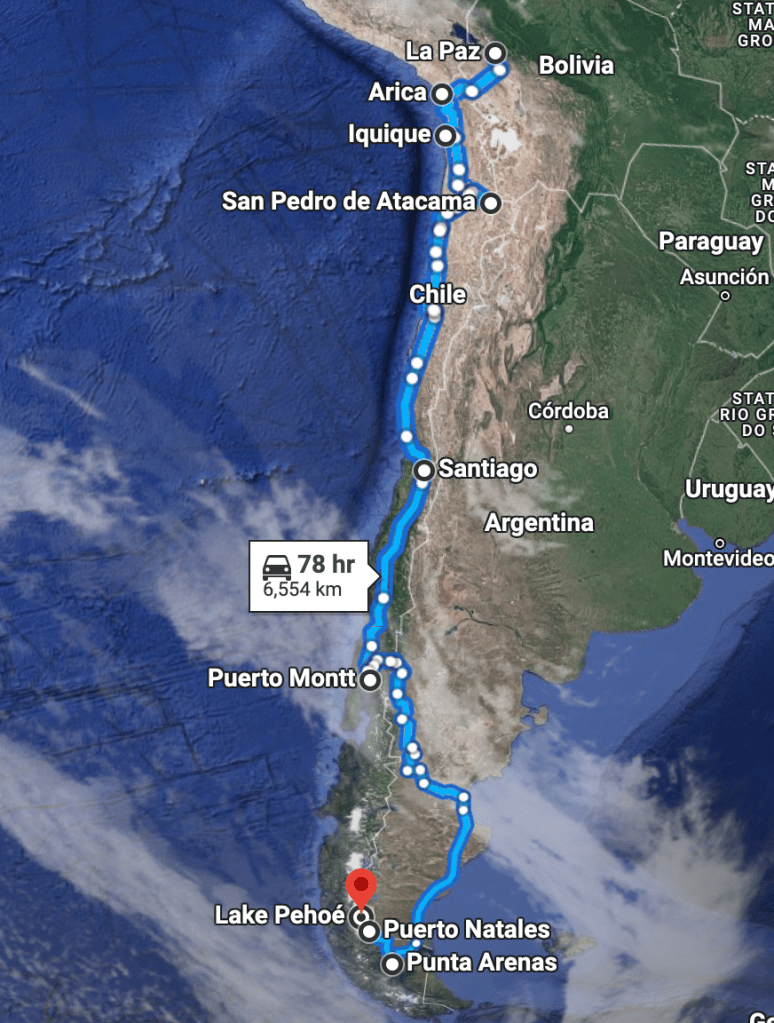

Stories from fourteen years of travel, starting on this page with ‘1993’, a journal of my travels through the Caribbean, Central America and the westside of South America that year.

Note: these stories are also in ‘talking book’ form at spotify and other podcast sites.

Here’s the link to ‘we’re only here once’ at spotify:

Cheers!

1993

Chapter One

Paris

I recognised the knife from when we were kids building hideouts in the park. It was a simple penknife, the type a dad might give his twelve-year-old son: sharp enough to whittle a twig, but not sharp enough to chop a finger off. This one had seen better days. Its blade was rusty and what had once been the sharper edge had nasty little divots. These details I knew because its ugly tip was hovering just a train’s-jolt away from my left eyeball.

I’d noticed the Africans huddled in the warmest corner of the carriage; about ten of them, sharing some kind of alcohol and sullen conversation. Their eyes glazed across the mostly empty seats. Over the last few years, I’d spent months travelling alone in east and north Africa, sharing hundreds of mini-bus rides with guys just like these. While they sure looked mean, I wasn’t going to be the racist. They were poor and outcast, and I owed them my empathy, not my fear.

When one of them meandered down the aisle to the other end of the carriage, his coat brushed my shoulder as the train lurched. A stench of dirt, sweat, urine, alcohol and marijuana lingered in his wake. On his way back, he reached behind my shoulder, grabbed the right side of my face, and pulled my other cheek hard against his hip. With my head trapped in this vice, his free hand swung the point of the penknife towards my left eye. “Give me your money”, he slurred in French. Beyond the blade, his fingernails were filthy and his smell filled my head. “I don’t speak French,” I mumbled, stupidly, in my schoolboy French. The knife was too close to bring into focus, but it was clear it would make a mess of my eye.

Trumping rational thought, my subconscious swung into inaction. Every muscle in my body went limp. His stinking, mittened hand began to cradle my chin as I slumped gently to the right. But the point of the penknife stayed wedded to my eye, gently swaying with each bump in the tracks.

Through my mental haze, from somewhere behind me, I heard someone shouting. As the African twisted toward the voice, the train burst from the dark tunnel into the surgical lights of a station. Blurred people-shapes flew by the windows as we slowed. The African let go of my cheek and began to shuffle unsteadily back to his seat. The voice behind me yelled again: “Jump off here with us!” and my brain and body re-engaged. I grabbed my bag, lurched to the carriage exit behind me, and escaped onto the platform.

Jimmy, whose voice had come to my rescue, and his fiancée, Karole, introduced themselves and checked I was okay. They’d have liked to help me more, but they were already late to their own engagement party. I’ll be fine, I promised them. It won’t be long till the next train. So they gave me their phone number and told me to call in a couple of days. But when they’d gone, the lonely silence overwhelmed me. A couple more Africans emerged from a passage down the platform and, to my shame, I lost my nerve.

Finding my way up to the street wasn’t easy. The underground walkways had few signs that made sense to me, and each airless, fetid corner was populated by still more impoverished Africans. My composure frayed further. When I finally reached the empty street, I found I’d arrived at the least populated exit. The dim street lights barely took the edge off the dark, and soft rain was falling. No taxis waited to whisk me to safety. I moved a few doors down from the station and feebly resolved to ask the first non-dangerous passers-by for help.

So, New Year’s Eve in Paris, eh? What a great idea. After six years living and travelling in Europe, how could I go home to Sydney, as I was planning to do this year, without visiting the home of the Enlightenment, the Revolution, the legendary writers and artists? And the home, no less, of young Alice and Marianne, the first people to pass my shivering figure as they headed to the station. Excuse me, I said, in my terrible French, is there a taxi stand close by? I don’t know, said Alice, but where do you want to go? The Latin Quarter, I said, but it was a semi-educated guess at best.

Typically for those freewheeling days, I thought I’d just fly into Paris on New Year’s Eve and, with the ‘Rough Guide’ I’d bought the day before, find a place to stay in the Latin Quarter for next to nothing. Ah, the idealism and chaos of youth. When I explained my plan, the girls led the way to a phone booth round the corner. Realising my French might not be up to the job, they waited patiently outside. But after watching my inept, unsuccessful phone-calls to a couple of the recommended hotels, they took over. Soon they’d found me a top-floor room not far from the Latin Quarter for only a few more francs than I was hoping to spend. Then came the proposal they’d been working on for the last few minutes: why didn’t I go out with them for New Year’s Eve? Have I ever known a more dramatic change in fortune? So we walked to the nearest main street and hailed a taxi to the hotel.

What the hotel manager must have thought as I checked in and went to my room with two young, attractive Parisiennes was completely mistaken. Let me disappoint you now: this is not the way this story goes. Shame on you for thinking it. The girls had been intending to spend New Year’s Eve together in the centre of town. Taking me along for the ride gave them some insurance against being harassed by other males… and somehow they perceived that I had the brains to know my place. And that’s the way it went.

We walked the streets of central Paris hand-in-hand, arm-in-arm, all night: across the bridges, along the river, through the parks. Through every street of the Latin Quarter; the Pont-Neuf; the Ile de la Cite, the Ile de Saint-Louis, the Champs Elysees to the Arc de Triomphe and back. We stopped at cafes for an occasional glass of beer or wine, a crepe, or a coffee to keep us warm and awake. At midnight there were some fireworks: real, not metaphoric. Paris, the city of love. Sigh. I drew admiring and bemused, mostly bemused, looks from men and women, young and old, every step of the way. “How have you got two?” jealous men would call. Hilarious. When eventually we were too tired and too cold to walk and talk any more, I rode the bus home with them to the Bois de Vincennes. By the time I got back to my hotel, alone and frozen to the core, it was nearly dawn.

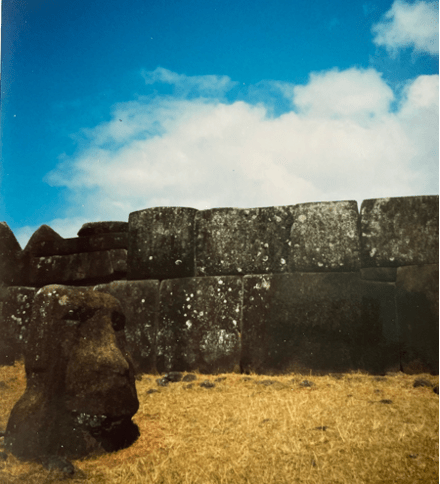

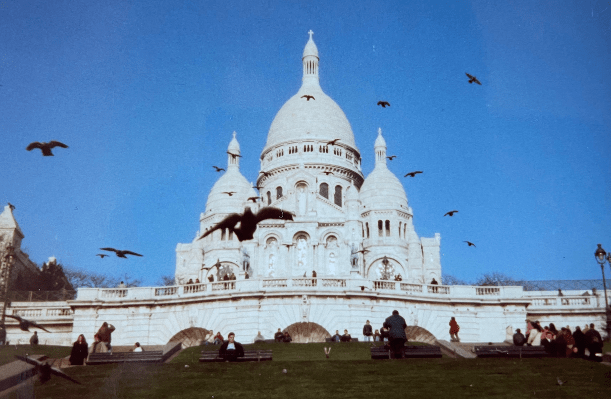

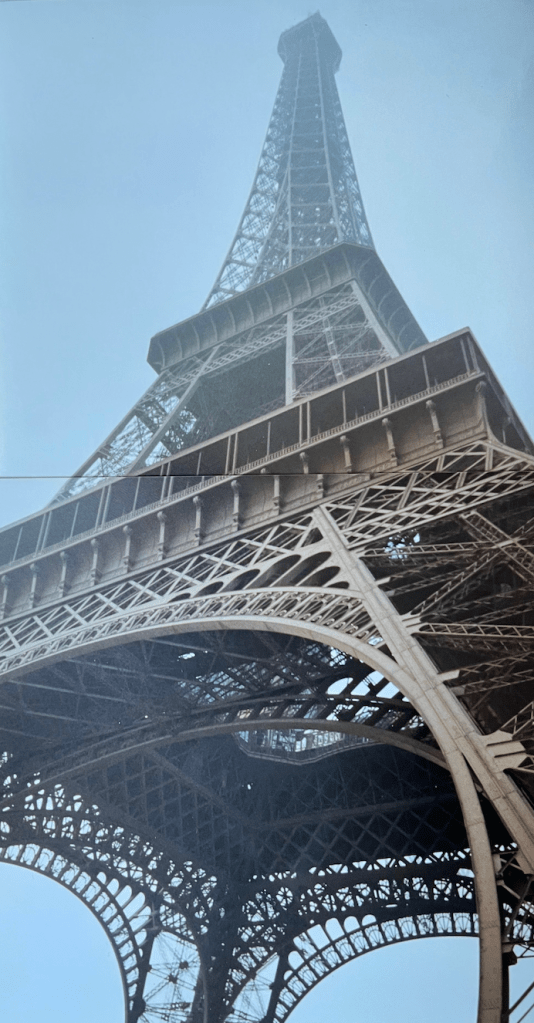

Nonetheless, by noon I was up and walking like a looney past the Pantheon, Notre Dame, up the Champs-Elysees again to the Arc de Triomphe, and to the Eiffel Tower. I decided the Louvre was boring, apart from Rodin’s ‘Thinker’ and the hordes of tourists grimly elbowing each other to take a photo of the monumentally underwhelming ‘Mona Lisa’. The next day it was sunny and cold and I marched across the river again, through Montmartre to Sacre Coeur and back.

Then Alice, Marianne and I met at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery to visit Jim Morrison’s grave. For any that don’t know, Jim was the charismatic lead singer of The Doors, the best of Los Angeles’ psychedelic bands from the late-sixties. In the early seventies Jim had moved to Paris and died mysteriously there at twenty-seven. Numerous signs graffitied on other people’s graves made Jim’s quite easy to find among the half million or so dead residents of the suburb-sized graveyard. Screeds of poetry, joints and half-bottles of spirits were left as odd offerings to Jim, the latter two being some of the reasons why Paris is his forever-home.

Melinda and Karen, two sisters from Sydney, arrive from Holland to spend a few days in Paris. We’d met in the hot, dry desert of southern Morocco the year before. This time we freeze. We shiver up the Eiffel Tower and through the brilliant modern art at the Pompidou Centre.

Jimmy and Karole, my saviours during the knife-in-the-eye incident, invite me to a magical dinner at her parents’ place. Her dad’s a pretty famous artist and the conversation is fantastic. On the way home, floating on great food, whiskey and wine, I take photos of street fountains turned to ice.

Like a centurion I trek repeatedly up and down the medieval, brick-paved Rue Mouffetard from my hotel to town and back. I gaze in awe at the Van Goghs in the Musee d’Orsay. I find bullet and shell holes from past wars in the old buildings around the Champ de Mars, and the best patisseries in the world. I come down with a terrible cold and a split in my lip so bad I can barely talk, let alone smile.

1993 was barely ten days old.

Chapter Two

Barbados

Barbados was a complete fluke.

I’d known for months that 1993 would be the year I travelled back to Sydney. I’d left my job, shipped home six years of memorabilia, and tried to tick off some final items on my ‘must-do-in-Europe’ list. But I’d left the actual details of my journey home completely undecided. I knew I’d go west through the Americas somehow; and, whether by air or sea, I’d need to cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But it wasn’t until I got back to London from Paris that I finally went shopping for options. At first it seemed the budget-friendly Aeroflot flight to Cuba might be best. The Cold War had been resolved a couple of years earlier by Russia’s attempt to open up and modernise, but nothing could eradicate Aeroflot’s ‘Plummet Airways’ reputation. Then British Airways had a flash-sale of the last few seats on a flight to Barbados at the end of the week. I couldn’t believe my luck.

A few months before, Mike and Margie, the parents of one of my Irish prep-school students, had told me: If you’re ever in Barbados in January, look us up. They knew I was planning to travel west from Dublin to Sydney sometime in the new year, but I’m sure they never expected me to rock up; and neither did I. But when I phoned them to say I’d be in Barbados on Sunday, they told me to come stay for as long as I liked. This was a better start to the trip than I ever could have planned.

In my last days in England, Mark, my old schoolfriend who’d moved to London years before, lent me his VW Golf to drive to Oxford to say a final goodbye to Grandpa, Lucy, Mallory and Jilly. On the Friday night, some lunatic with a knife (yes, the second in a fortnight) attacked Mark’s car while it was parked safely under a streetlight just off Woodstock Road. They slashed the soft-top roof and one of the tyres; and they took a few CDs and some coins from inside. When I telephoned Mark to tell him, he said No worries; it’ll be covered by insurance. But a few minutes later he called me back to ask if the golf clubs were still in the boot. What golf clubs? I said, and there was a pause. Never mind, he said stoically, I forgot I’d left them in the car. When I got back to London, I found they’d been custom-made in St Andrews and Mark wouldn’t take any money in compensation. I’m still thinking of a way to pay him back.

The nine-hour flight from London to Barbados was the biggest jump towards Sydney I’d make for the rest of the year. It was also the biggest jump in seasons and cultures. As the humid, tropical air enveloped me at the plane’s exit, and the exclusively dark-skinned airport staff welcomed me to their island, I felt as much a foreigner as it was possible to feel. In a corner of the world where the majority of the population is descended from slaves brutally transported from West Africa four hundred years before, I looked forward to losing my luminescent Irish-winter pallor as soon as possible.

Given the amount of luggage I had and the quirks of the public bus system, a taxi from the airport to Mike and Margie’s house in Gibbs Bay was the only viable option. My connection with the Afro-Caribbean taxi driver got off to a rocky start when I insulted him by trying to negotiate the price. However, once we got going and he discovered I was Australian, we bonded over cricket. Unknown to me, a few hours earlier the West Indies’ national team had beaten their arch-rivals Australia in the final of the One Day series played in Melbourne. The driver had sat up all night listening to every ball on the radio, and as he drove he recounted every twist and turn of the match as if he’d been playing himself. The timing of my arrival couldn’t have been better.

As we rattled up the west coast, the bright, fragrant, warmth of the island flooded the old Chevrolet’s open windows. We arrived after a trance-like forty minutes, and I wondered if I’d been pranked: Mike and Margie’s house was more an estate than a holiday home. And here, up the drive, came the house staff to meet me. Carrying my bag and surfboard, they led me through the tropical garden, past the pool and up the wooden stairs to the balcony beside my room. Through the casuarina trees, the Caribbean stretched from gleaming aquamarine to its sapphire horizon. Tiny waves whispered a cartwheel’s distance from where our garden turned to white-sand beach. Mike and Margie will be home in an hour or two, Mr James, one of the ladies said. Can I bring you a beer? You little ripper.

That afternoon I discovered I’d stumbled into the biggest week of 1993’s Bajan social calendar. This was Robert Sangster’s annual amateur golf tournament at the Sandy Lane resort. Unknown to me while I was teaching their son, my hosts were an integral part of Sangster’s legendary Irish horse-breeding-and-racing circle. On holiday from being parents at a strait-laced private prep school, Mike and Margie were hilarious. Mike raced about the place in his mini-moke, promising any conceivable wrangle with the police could be solved with a jovial “Good c*nsternoon, arsetable!” This apparently would get everyone laughing and all would be forgiven. He might have been right.

Since I was now suddenly their houseguest, they included me in everything. I was too late to get a start in the golf, which was just as well. But every night they included me in the epic dinners at way-out-of-my-league restaurants like Carambola, La Cage aux Folles and 39 Steps, where every member of the circle celebrated the wins and losses of the day. Another night, the Sangsters threw a party at their house (well, estate; it sold a while ago for something like $50 million). I nearly committed what would have been social suicide (if I’d had a social entity to kill) when I accidentally danced with Robert Sangster’s wife. After half a song I realised who she was and made my excuses.

It was bizarre to be involved in conversations and debates with these people from a world so far removed from my own. Perhaps they found this nomadic, hippy schoolteacher with no dress sense, attempting to find his way around the world on the smell of an oily rag and no prospect of an income, just as fascinating as I found them. I was honoured to be as welcome as they made me feel.

Among the hundred others, there’s no doubt the peak moment in the miles-out-of-my-own-orbit genre came when I discovered Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, undoubtedly one of the twentieth century’s greatest musicians, and quite possible a god, sitting directly in my eyeline at the restaurant dinner table next to ours. How should I react?

Obviously, asking for an autograph was completely the wrong thing to do. Jimmy was at a table for two with, it must be said, beautiful company. He didn’t want to be pestered and I didn’t want to be that guy. He didn’t need a complimentary drink or an extra pudding from a random diner, and I couldn’t have afforded to pay for them anyhow. Then it hit me, this would be my simple gift: I’d pretend I didn’t know who he was. I congratulated myself on this decision: how many others would have thought to give instead of take? Through all three courses, I kept my eyes from roaming to his table.

But a final challenge came as I returned from the loo several magnificent wines later. Jimmy was walking straight toward me, his rockstar gait exceeding all expectations. He was even taller and his arms even longer than I’d thought. If we weren’t careful, our shoulders would touch. Our eyes met for a second, probably more. He smiled and nodded. I smiled and nodded back as if he was any other bloke down the pub on a Sunday afternoon. I think I may have offended him.

While the week in Gibbs Bay far exceeded any expectation I might have dreamed up for the start of my journey home, my gaze had already been distracted. On my second day, Margie lent me her car to explore the island. Armed with ‘Surfer’ magazine’s ‘Surf Report’ on Barbados, I charted a clockwise course around the coast.

Before the age of google, google maps, and cameras that live-stream vision of nearly every coast on the planet, The ‘Surf Report’ was the only source of information about foreign surf-zones. Each ‘Surf Report’ consisted of just two yellow A4 pages of roughly typed information about that edition’s destination. In preparation for this year’s trip, I’d spent a small fortune, via bank-cheque and international post, on about thirty editions of ‘The Surf Report’ to give me intel on just about every surf destination to which the winds of fate might take me.

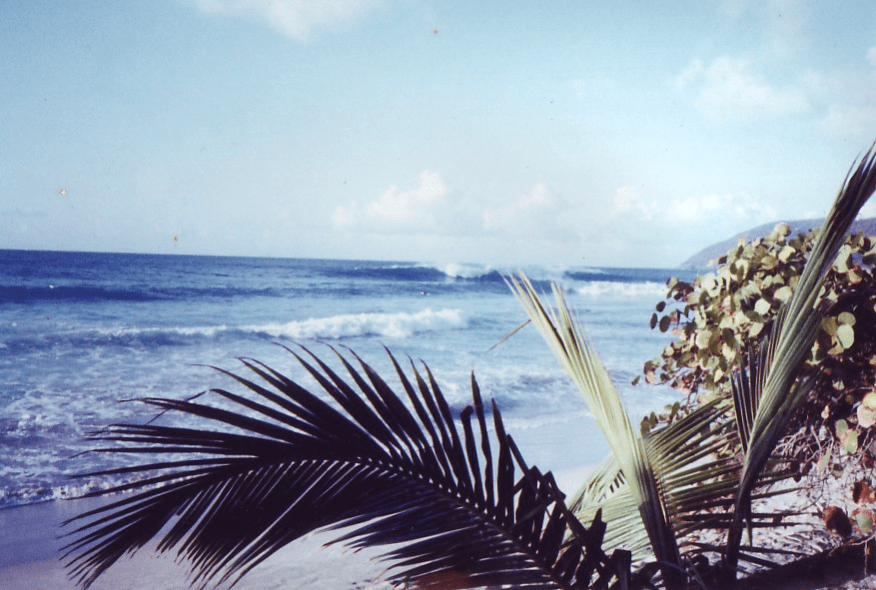

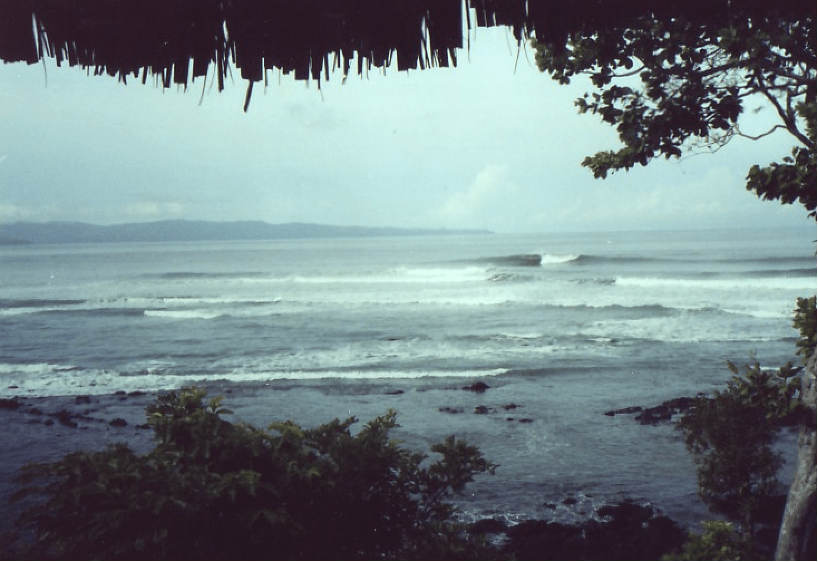

The ‘Surf Report’ on Barbados advised there were good waves on every coast of the island. But the best of them was called Soup Bowl, on the east coast at the little village of Bathsheba, an hour’s drive across the island from Mike and Margie’s place. Halfway through my first surf at Soup Bowl on that second day, I knew I had to live in Bathsheba for a while. On the way back to Gibbs Bay that afternoon, I discovered ‘Matilda’, an empty yellow wooden shack with a picket-fenced lawn facing the ocean just a minute’s walk from Soup Bowl, and I knew I’d found my next home.

But when I eventually tracked down the landlord of ‘Matilda’, a gruff old Afro-Caribbean man in a cabby’s hat named Mr Bostic, I made the fatal error of trying to bargain on the price. (You’d think I would have learned from the first day’s taxi debacle). If you want to argue about the rent, you can find somewhere else to stay, Mr Bostic said abruptly; and he walked away with a wave of his hand. Oh crap, I’d really crashed the car. After a restless night back at Gibbs Bay, I drove back over the hills to Bathsheba, eventually found Mr Bostic, and made a grovelling apology. Oh, you’re from Australia, he said. We beat you last night! We beat you by a run! Oh, your last batsmen nearly gave me a heart attack, but we beat you by a run! He expected me to know, but shamefully I didn’t, that a few hours earlier the West Indies had won the Fourth Test in Adelaide by a single run after the Australians had nearly pulled off a miracle comeback win. I don’t know how he would have treated me if the West Indies had lost, but after describing every twist and turn of the final day’s play, he agreed to rent me ‘Matilda’, at his price, and we shook hands as friends. I was home.

Within an hour of moving in, the silhouette of a massive, dark rasta man filled one of the windows that looked out to sea. I was playing my tiny traveller’s guitar in the front room. What you play? he said quietly when I rose to greet him. Taking this, accurately, I think, as my audition for acceptance into the village community, I chose Bob Marley’s ‘Get Up, Stand Up.’ Under the pressure of his presence, it was probably the best I’ve ever sung it. When I stopped, he deadpanned You can play, and left. He never visited ‘Matilda’ again, but I think I saw him leading his goats through the village a couple of times.

In his place, however, came a handful of the other local boys, all Afro-Caribbeans, who invited themselves to hang out on ‘Matilda’’s front verandah every day. At around mid-morning on my first day there, they sauntered off the road, across my lawn and onto the verandah, with its unrivalled view of Parler Beach and the only road through the village. They introduced themselves but avoided eye contact and kept their distance, even while we shared the same space. If they needed, they helped themselves to my food, but never too much of it. They were kind of friendly, but I understood that, even though I was paying the rent, this was their place. I was just a visitor. They called me a ‘soft haole’, which was the local term, borrowed from Hawaiian surfer slang, for a white visitor who didn’t cause any harm. It was kind of denigrating, but approvingly so. These guys were heavy; they would have killed me in a fight. They were poor and most likely always would be. They lived hand to mouth and, when necessary, stole. Another surfer, Chuck, a staggeringly unabashed racist from Florida, turned up in a smart hire car, rented a fancy house up the hill, and started calling the local boys off waves at his first surf at Soup Bowl. He was robbed of everything except the clothes he was wearing within twenty-four hours of his arrival. I don’t know if it was the guys I knew or someone else. In retrospect I reckon my house must have become a protected area. If they or anyone else stole from me, I’d be forced to leave the village, then they wouldn’t be able to hang at ‘Matilda’ anymore! I was proud to be a ‘soft haole’.

Mr Bostic had warned me about only one of the locals: Watch out for Snake, he said. He bite ya. Sure enough within a day or so Snake came to the front door – alone, as ever, for the other locals avoided him – to ask if I needed any dings in my board fixed. There were a couple of cracks on the rails, and I thought it would be wise to support local industry, so I gave him the job. Secretly I hoped that my standing as a ‘soft haole’ with the other local surfers would keep Snake honest. He asked for payment in advance, so he could buy the materials, he said. I agreed to give him half the fee, telling him I’d pay the balance when the work was done. He vowed to return my board, fixed, first thing the next morning. But an hour after dawn the next day, the surf was cracking, but there was no Snake and no board.

One of the boys on the beach gave me directions to where Snake lived up the hill. When I found the simple house, there was my board, neatly fixed, lying on the dewy grass outside. Snake was inside with another guy, a pimply, pasty, dodgy-looking white American. They were both awake, despite the early hour. Snake took my cash, the balance of my payment, and handed it straight to the American. From a small plastic bag in the American’s pocket, they each chose a tiny rock. In turn, they lit these rocks in a pipe fashioned from alfoil and an empty matchbox. The small rocks popped and cracked and made a strange smell and after sucking up the smoke, each of them sat back, stunned. I made my excuses, told them the surf was pumping, and fled to the beach with my board.

The day I’d met Snake at ‘Matilda’, he’d told me he was one of the original gang of local boys who’d copied the tourists and taught themselves to surf. It was hard to believe. I’d never seen him anywhere near the waves. But a few days later, Snake came to ‘Matilda’ to asked if he could have a go on my board. It was a reach to trust him again, so I walked with him and my board to the Soup Bowl. Snake paddled out in filthy jeans instead of boardshorts, but as I watched from the rock, it was easy to see the remnants of his addled skill. This despite the ruin his life had become.

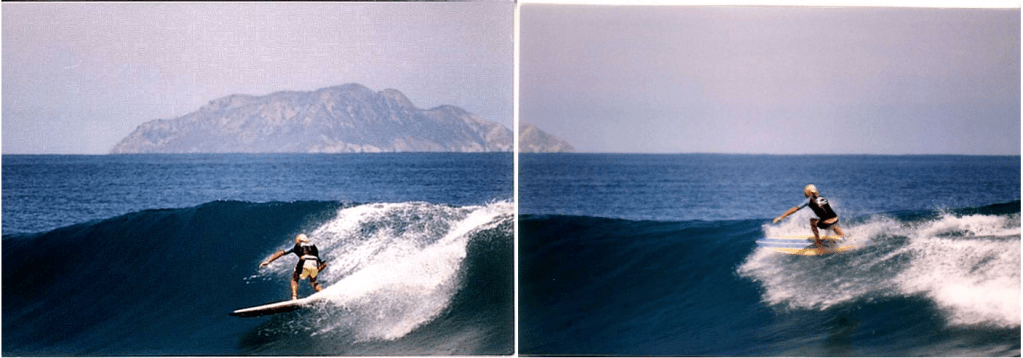

Mark Holder, on the other hand, not only danced with the waves, he flew. The other local boys, especially Zed and Arlon, surfed every day. Mark only appeared the first day it got big and nasty, after a big storm had passed far away to the north. These occasional groundswells were far bigger and more powerful than the everyday windswells I’d surfed so far. I was on the beach resting after an early morning surf that had tested the limits of my ability, when this Afro-Caribbean bloke with sun-bleached dreads jogged past me and paddled out. With his hair still dry, he chose his first wave and took off ten metres further up the reef than was humanly possible. He air-dropped, turned square off the base and disappeared as the wave turned inside out. He reappeared at the speed of sound and levitated onto the roof of the wave, skating weightlessly for longer than physics would allow, before airdropping down to reconnect with the face. It was the best surfing I’d ever seen.

The next day the waves were even bigger and I was giving it another crack. For the first hour, with Mark’s encouragement, I scratched into a few of the biggest waves I’d caught in years. From close up, his surfing was even more spectacular and artistic. As the tide ran out, the waves got steeper and the other surfers went in. James, he said, every wave’s like this, and he made a cliff shape with his fingers. But I didn’t heed Mark’s warning. A wider one crested out the back and I paddled out to meet it, turned round and took off. It was a long way down; much, much further than I’d anticipated. I arched my back, trying to reconnect the inside edge of my board with the vertical face. The wave formed a second sky as I fell. When I finally hit the water, it snatched me up and hurled me into the reef. Thank God my buttcheek took the impact. I walked up the beach a legend. My housemate, Joy, told me it was as big as a truck and wouldn’t stop talking about my bravery. But I wasn’t proud of overstepping the limits of my ability. It wouldn’t be the last time that year.

Later in my stay, Mark asked me a favour. Two old friends of his were flying in from a neighbouring island. Could I help him collect them from the airport in my rental car and show them round? No worries. It was an honour to be asked. At the airport, Mark’s two friends turned out to be two French girls, Valerie and Marie. Valerie was from Martinique, an island not far from Barbados, and Marie was… holey schmoley, I recognised her: the beautiful wife of the world’s best surfer at that time, Tom Curren. Mark had entrusted me with the safe-keeping of the First Lady of Surfing. For a few days we day-tripped round the island, surfed Soup Bowl, somehow by ourselves, and on Valentine’s Day we all shared electric blue waves at a south coast point called Freights.

The other member of our party was Joy, my housemate. Joy was one of a very small societal sub-group in those days: a woman who surfed. Sure, there had been a women’s world surfing champion every year since 1964, but to the average surfer, women who surfed were very rarely seen. In fact, come to think of it, before those days in Bathsheba I’d shared just one single session with a female surfer. It was at Fairy Bower at Manly one morning in 1983 when I should have been at uni. And what a surfer she was! It was Pam Burridge, then aged about eighteen, and she was ripping. It was no surprise she won the women’s world championship a few years later.

Somehow the 1970s to 1980s society I grew up in didn’t see surfing as something women did. Why ever not? What was not to like about sharing waves with women? Why was surfing some sort of man-shed? Come to think of it, up until the 1970s, there were ‘Ladies’ Lounges’ in many pubs so men and women could drink in their own company. These were still the dark ages of gender equality and social inclusion. These were also the days when middle-aged drunks were a familiar sight, even in daylight hours. Were these the men who’d fought in World War Two and returned to society brutalised and broken? Had they been brutalised by their fathers who’d been brutalised by World War One? Was it the example set by the older males that led the younger surfers to belittle and intimidate any woman who attempted to share the waves? A recent documentary called ‘Girls Can’t Surf’ explores this period in surfing and how women eventually gained the respect of their male peers.

Anyways, back to Joy and ‘Matilda’.

Joy was Philipino-American, originally from Virginia Beach, but she’d moved to Hawai’i to surf. She found work at one of the posh hotels on Kaua’i and was living her dream until in September 1992 Hurricane Iniki flattened the tourist industry, leaving Joy long-term unemployed. With months to kill before she could return to work, she’d set out to make the most of her lay-off by surfing the world, or as much of it as she could before her savings ran out.

Joy was walking a tightrope in a few ways. First, she had to watch every cent she spent. Second, she was an outsider in a chauvinist culture. And third, she was determined to retain emotional independence. For the first months of her trip, these challenges had been met by sharing the adventure with another Hawai’ian female surfer. But when her friend returned home, Joy needed a new travel partner. With no other surfing females available, she chose me.

I was honoured to be her travel partner, but it was a bit awkward for both of us. I had to suppress the truth that I found her attractive. Yes, I know these days we’re all so evolved and can negotiate these delicate situations as if we were picking apples, but this was thirty years ago. It was hard sharing these wonderful, unique days with a woman who I had to keep my distance from. It was tricky for her too. While she sometimes wanted to exercise her independence, she didn’t want me to feel neglected and exploited, especially as she knew that my presence saved her from the advances of other maIes who wrongly presumed she was my girlfriend. In our time together, several other men tried to get close, but she artfully kept us somewhere between hand and arm’s length. It was a complex situation, but I so valued our time together.

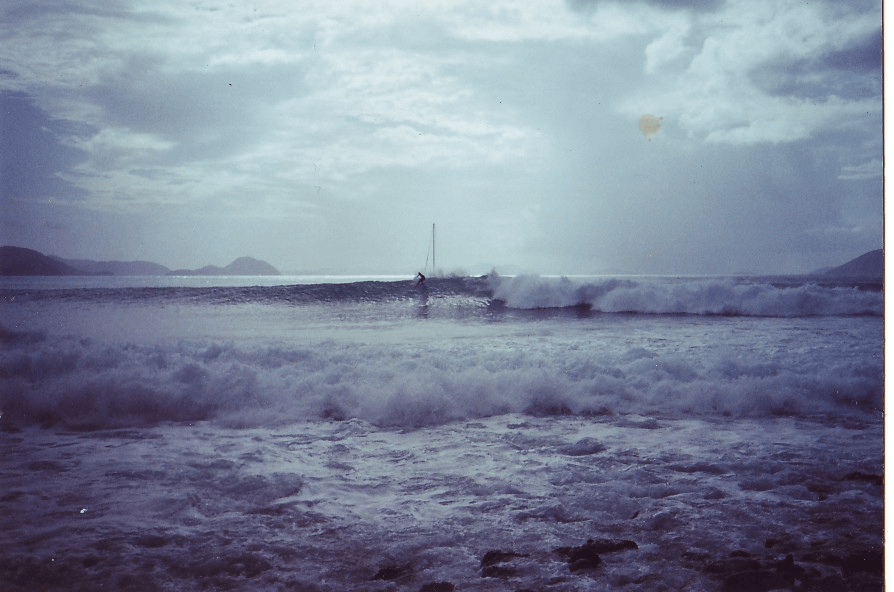

Each day began with a glassy early morning surf at Soup Bowl. By mid-morning, the trade winds blew in like clockwork, ten to twenty knots from the northeast, until the late-afternoon calm. By 4pm the wind-swell had settled into sets and we’d surf long, powerful, glassy waves until dark. The last of the wind-swell would be there the next morning, then the cycle would begin again: a cosmic wave machine.

In between surfs we’d eat, rest, play music, talk and write diaries. No-one went to town and there was no work to do. The furthest we went was Mrs Marshall’s bakery up the hill for bread and currant buns, or the Rum Shack for beer. Most nights we’d be asleep by ten to be ready for the early surf. Only one night we stayed up till after midnight. We built a fire on the beach in front of Soup Bowl and watched the full moon rise. When I suggested we go for a surf, the local boys warned me “the duppies’ll get ya”. (Duppies are water spirits; the souls of those who’ve drowned, apparently.) I thought they were only winding me up, and I dared them to come out with me. Only Arlon took up the challenge, but as soon as he was out the back he freaked out and in raced to shore in genuine fear. Somehow I survived another few minutes before surrendering to superstition… or maybe the sharks in Barbados are nocturnal.

Duppies is the name given to one of the island’s wildest waves, breaking a long way out to sea from steep cliffs on the northwest coast. The local boys came for the drive in my car, but wouldn’t dare surf, even though the water was mid-sunny-day-crystal-clear. Federico from Argentina caught the best waves that session. Maycocks was another right point we surfed; and when another big groundswell arrived from the north, there were perfectly shaped, powder-blue, waves on Gibbs Reef, just up the beach from Mike and Margie’s, where I’d stayed the first week. In near darkness that evening, I split the peak of our last wave with the drummer from the Tom Tom Club.

On Saturdays the locals played cricket on every available patch of semi-level turf. Each bowler steamed in off a long run and the batsmen tried to hit every ball beyond the horizon. Success and failure were met with rowdy cheers or heckles from the women and children round the boundary. On Sundays the church next door to ‘Matilda’ rocked with a hundred voices in three-part harmony. One day, Mike and Margie came to lunch at ‘Matilda’ and had such a good time they stayed for dinner as well. I was glad to offer some hospitality in return for all they’d given me in my first week on the island.

After a fortnight, I drove Joy to the airport for her flight back to Virginia. On the way, she suggested we stop at one of the beaches on the southern shore. We talked for an hour or two then watched her flight disappear into the sun’s glare. Joy ended up staying in Barbados for a fortnight longer than me. When I left, she told me to phone her in a couple of months to see if we might meet later that year somewhere else in the world.

Barbados had given me a decade’s-worth of adventures and waves. If I’d had to go straight home to Sydney, I could have lived with that. But knowing it was unlikely I’d ever see this corner of the world again, I bought a Leeward Islands Air Transport excursion ticket that would take me to any three of the other Caribbean Islands. Though it felt like gluttony, I chose Tortola, Guadeloupe and Puerto Rico.

And what about those other twenty countries between the Caribbean and Australia? I didn’t need to be back in Sydney for another ten months… if I could make my savings stretch that far.

.

Chapter Three

Tortola and Guadeloupe

“Tortola.”

That’s all Mark Holder said when I asked him where else I should go in the Caribbean. Mark was the best surfer in Barbados, so I was all ears. He didn’t say if Tortola was a town, a beach, an island or the name of a wave. And the conspiratorial, reverential way he said it told me I’d have to join the dots myself. I’d never heard of it and wasn’t sure how to spell it, but that night’s research revealed it was one of the British Virgin Islands, eight hundred kilometres northwest of Barbados. Cheers, Mark! Has a single word of advice ever given me more?

My flight to Tortola arrived late at night and it took a couple of hours for the friendly airline staff to declare that, yes, my backpack was officially lost. Luckily, the backpack contained nothing essential. Most importantly, I still had my surfboard. All unreplaceable luggage – passport, camera, surfboard fins, ‘Surf Reports’, used camera film, money and so on – travelled in my money belt or my carry-on daypack. The backpack carried only clothes, a cheap tent and a couple of guidebooks to places I may or may not visit in the coming months. So living without it for a few days would be no drama.

The major setback was that I had to stay that night at the over-priced airport hotel to see if my pack turned up the next morning, as the airline staff thought it might. Trying to get some value out of the money I was wasting, I gave American cable television a try for the first time. All fifty-plus channels presented nothing remotely entertaining: just news, canned-laughter sitcoms, cliched conversations about basketball, and advertisements for sugary foods and weight-loss medications.

The next morning, I found the backpack was still lost and probably would be for some time. With the ubiquitous ‘have a happy day!’ smile, the airline staff gave me a cheque for fifty US dollars to spend on ‘essentials’. But that didn’t cover the cost of last night’s hotel, and it didn’t cover the cost of a taxi ride across to the surf coast of the island. So in the rising heat of a blue-skied day, I walked a couple of kays from the airport and waited an hour or two to hitch a ride.

Arriving in Apple Bay, the village at the centre of the island’s small surfing world, I saw head-high waves breaking just out to sea. But first I had to find a place to stash my stuff. The cheapest accommodation I could find was an airless fleapit for another ball-crushing fifty US dollars a night, at least five times over my projected budget for the year allowed.

Resigned to my stay on Tortola being a short one, I went for the sweatiest surf of my life. Unpacking my surfboard from the yellow-fabric-lined-with-bubble-wrap sleeve that passed for state-of-the-art boardbags in the late 1980s, I discovered my boardshorts were the one essential item that was trapped in my lost backpack. The most viable alternative to surfing nude was to wear the crusty full-length wetsuit I’d brought from Sydney six years before. While I thought it might come in handy in the latter stages of my journey home to Sydney, it’s ongoing purpose was to serve as extra padding for the rails of my board in the bubble-wrap sleeve. Since it was designed for the Sydney winter, not the Caribbean spring, the wetsuit was going to induce hyperthermia, so I borrowed scissors from the unfriendly landlady, and chopped the wetsuit’s arms off above the elbow. I thought about chopping the legs off too, but a few months later I was glad I hadn’t.

Thus resplendently attired, I introduced myself to the Apple Bay reef and its inhabitants. The wave was a gentler version of Soup Bowl in Barbados. Every morning started waist-high and glassy, breaking right and left across the friendly reef: a perfect way to greet the day. Between nine and ten, northeast trade winds blew in until around four. When the wind dropped in the evening, the wind-swell formed into increasingly well-spaced, head-high-plus waves. From lunchtime until it got too dark to see, you could surf to the music floating across the water from the Bomba Shack, an open-walled pub built of driftwood just above the high tide line. We surfed good Apple Bay nearly every day for four weeks, and on six of those days, when a groundswell swung down from a distant storm to the north, it absolutely pumped. Easy fast take-offs led to two or three fast, long-walled sections, with room for a cutback between each. If it was small, the left let you practise riding switchfoot, or taking off fin-first.

My surfboard, named Byron, loved the Apple Bay waves. Warren Cornish from Byron Bay had shaped her for me back in late-1987. So Byron was five years old and a bit road-weary by the time she reached Tortola, but she still surfed well. For the four years prior to getting Byron, I’d ridden an antique Russell Hughes Crystal Vessel from late 1967. As much as I loved it – oh, the things the massive deep vee and bendy fin let you do on a wave – the Vessel wasn’t an international traveller. At over two and a half metres and nearly ten kilograms, it would cost me a fortune in excess baggage. Further, the Vessel sported an unremovable thirty five centimetre fin that would be irreparably destroyed within a few flights. So I’d asked Cornish to make me a board that was as big as would fit into the lain-down passenger seat of my friend’s yellow mini; and strong enough to survive the roughest treatment by man, wave or reef. Byron was a statuesque seven foot two with three thick stringers, a wooden tail-block, two leg-rope plugs and loads of fibreglass. Her paddle-speed gave me mobility round the line-up and made any wave catchable, big or small. She flew off the bottom, then went faster and faster with each pump; but she turned on a dime and hung on in the barrel.

Boards like Byron came to be known as ‘mini-mals’, which was short for mini-malibus, the nickname for 1950s and 60s longboards. ‘Mini-mals’ were pronounced uncool by mainstream surfers, despite one or two of them nearly always commenting that my board (quote) ‘really suits the conditions today’. Thirty years later, boards of this type are called ‘mid-lengths’ and are state-of-the-art cool thanks to the classically brilliant surfing of ‘free-surfers’ such as Torren Martyn, who have thrown off the dual shackles of competitive surfing and the crippling conformity regarding equipment to which many surfers still submit. For the previous five years, Byron and I had caught waves together in England, Ireland, France, Portugal, Spain, Morocco and the Canary Islands. Apple Bay soon became one of her favourites, alongside Barrtra, Coxos, Anchor Point, The Bubble and Soup Bowl. And then she surfed Cane Garden.

Cane Garden Bay was seven kilometres northeast from Apple Bay. It was the archetypical tropical paradise of sparsely populated, steep wooded hills falling into a tranquil turquoise sea. (Well, sorry for the cliches, but that’s what it was, and still hopefully is). Normally it was an occasional anchorage for a handful of the luxury yachts that frolicked round these islands. But, as I soon learned from the few local surfers, when the big groundswells rolled down from the northwest, the bay’s northern point produced one of the best waves in the Caribbean.

After a week of good to epic waves at Apple Bay, we heard a groundswell arrive in the middle of the night. At dawn, Johnno and I set out to walk to Cane Garden with our boards. After an hour of walking and half-running while watching the new swell surge onto the beaches and reefs, we got lucky with a lift on the daily milk truck and arrived to be nearly the first surfers out. It was still a bit raw and wild, but if you got a good one, you’d race a three-metre-high face for two hundred metres at warp speed. The afternoon session was even better: slightly smaller, but more lined up and groomed by the every-day trade-wind. The middle section was hollowest and you could hear the rounded river stones and old coral heads rolling against each other just beneath your fins. The waves turned electric blue and ruler edged, literally the waves of my dreams. In the evenings the local pelicans gathered out the back, just outside the first peak. A few times as I took off just inside them, they spread their wide wings and took off in front of me with the updraft from the wave. They’d glide a few metres ahead in perfect formation through the first section, then bank back out to sea as the wave shot into the hollow section near the rocks. It was bonkers; surreal. We had about six days like this.

Bizarre, also, was a few years later finding a photo of me surfing Cane Garden’s inside section stuck to the fridge in a beach house in the far south of New Zealand’s South Island, not far from Antarctica. The day I found the photo, I’d been surfing a left point called Porridge with a bloke called Wayne Hill. We were the only surfers for a hundred kilometres so we soon got to chatting. Afterwards, he invited me back to his house for a cuppa to warm up. As we shared stories he stopped and fetched a matchbox-sized photo from the side of the fridge. Is this you? he said; and it was. One of his friends had been crewing a yacht in the Virgin Islands and had sailed into Cane Garden that day. He’d taken a quick snap while they’d dropped anchor. He had no interest in the surfer but he knew Wayne would be interested in the wave. He’d had a mini-print made and sent it with a letter to New Zealand. I’m hardly ripping, but I reckon the photo captures a little of the speed and beauty of the wave.

The highlight of the social life in Tortola that month was spending time with John and Nancy. Johnno was a Bondi boy who’d moved to New York, got a green card, then worked as a rubbish collector to fund surfing trips to the Caribbean, Central America and beyond. I’d hardly spent any time with Australians for over six years and hanging out with John was as good as being home again. Best of all, Johnno and his girlfriend Nancy rented me a room for twenty bucks a night in a really nice house they were long-term renting in Long Bay, just a scenic ten minute walk over the hill from Apple Bay. Without that room, I couldn’t have stayed on Tortola for more than a week, so I owe most of these waves and experiences to you, Johnno and Nancy. Thank you! I hope the last thirty years have treated you well.

John caught me up with a lot of the Australian bands I hadn’t yet heard: The Cruel Sea, Celibate Rifles and the Died Pretty, among others. When his mate arrived from Australia with gifts of Tracks (surfing) magazines, Tim Tam biscuits and Three Threes pickles, John shared the precious treasure with all of us. On the other side of the ledger, like a true Aussie, he didn’t hold back when I thoughtlessly caught the cracking left at Apple Bay he’d waited an hour for. Then when I suspended myself from surfing the next day, he told me to get over it and get back out there. His girlfriend, Nancy, was a New Yorker who tolerated me for weeks and treated me like family when she cooked great meals. She also guided me to the island’s only clothing shop where I spent the airline’s emergency fifty bucks on the the bright-yellowest, most expensive, pair of boardies I’ll ever own. They were two sizes too big, meaning my bottom turns had two meanings from then on.

Another faction of our community were the surfers from the US east coast. A couple of them had sailed their own boats solo down to the island and had hair-raising stories of being caught in storms so fierce their boats had turned-turtle. They were a tough crew. When I flew to Puerto Rico in the last week of March, I met a lot more of them.

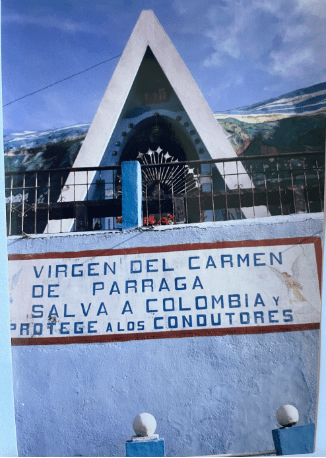

Before going to Puerto Rico, though, I’d better not forget Guadeloupe. This butterfly-shaped island lies halfway between Barbados and Tortola, so it made sense to have a short stopover there. All the Caribbean islands have interesting and often sad histories, but Guadeloupe has one of the saddest. After Christopher Columbus had arrived there in 1493, Spanish attempts to colonise the island were fought off by the indigenous people for over a hundred years. In the 1600s, however, France replaced Spain as the island’s colonial repressors and within a few decades, most of the indigenous population had died from gunshot wounds and European diseases. To replace the lost indigenous population, West African slaves were imported to build an obscenely lucrative sugar industry. In 1802, while France claimed to have achieved democratic freedom in their own country, they brutally suppressed a slave rebellion in Guadeloupe that concluded when the rebels collectively blew themselves up along with their store of gunpowder. In 1848, when slavery was finally outlawed in the French Empire, indentured labourers, who were slaves in everything but law, were imported from India to fill the labour gap. Just one of so many examples of how enlightened Christians brought joy and meaning to the rest of the world through capitalism. Um… not.

Being a French territory, Guadeloupe didn’t cater for vagabonds like me aiming to live on scraps. Accommodation, car hire, food… everything was beyond my means for any more than a few days. Nonetheless, I had some great times. I walked two hours in thongs (a poor choice, I discovered after half an hour) to ride head-high left-handers in what appeared to be a tropical aquarium at Petit-Havre. When I hired a car for a few hours on my last day, I found a great righthander all to myself and miles from anywhere at Pointe Plate on the northeast coast.

Christian, my host at the pension, also served as tour guide when he wasn’t working. He took me to Le Moule, the island’s everyday wave, and when a couple of other guests arrived from France, he loaded us onto the back of his ute and took us to Basse-Terre, the wild, beautiful southern half of the island, where we swam under the Chutes de Carbet waterfall. He also took us to someone’s house-party where I danced myself lame to local drum music I’ve searched for ever since.

And on that musical note, let’s go to Puerto Rico and learn some Spanish. The trip’s about to get rowdy.

Chapter Four

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico was loose; too loose. It was only a hundred and fifty kilometres east of Tortola across the Caribbean Sea, but it was a whole ‘nother universe.

For surfers from the US’ eastern states, the Rincon / Puntas area in the northwest corner of the island had been a surf-party-draft-dodgers’ paradise since the mid-1960s. By 1968 it was high enough, pun intended, on surfers’ radar to host the World Surfing Championships. Being a US territory, but not a state, it was a bit like the Wild West. Every day held the possibility of the best or the worst of times, or both. Some of the local gringo crew had come for the surf; some had come for the parties.

The gang I spent most time with seemed to have walked straight out of songs Bruce Springsteen wrote about his New Jersey hometown on his first few albums. They said things like ‘You can’t read a book without turning the pages, you know what I mean, pal?’ Time with them was one long crack-up. They owned surfboards but never took them in the water. Often they’d be settling into party-mode before lunch-time. I’m not saying that’s wrong, it just meant we didn’t get much done.

Two of them were terrific guitar players and a couple played harmonica. I hoped our Rincon gang could make a band and look for work in the local bars and restaurants. I’d spent the downtime in Barbados and Tortola writing songs on the cheap travel guitar I’d bought in London. In my idealistic haze, I planned to record them somewhere, somehow, on the road. But though a dozen inspired jams went down in houses and bars and on beaches, we never organised a real rehearsal or a gig. And despite my Plan B to make an album by simply recording one of our jams down at their awesome farmhouse in the valley, that never happened either.

Pretty emblematic of this state of mind was when an American guy we half-knew came to find us in a bar called, appropriately, Trouble in Paradise, or TIPS for short. “There’s an open-mike night tonight up in Aguadilla; I can drive you there”, he told us. So we gathered our instruments and climbed into his car: two in the front and four in the back. The road from Puntas, our village, to the main road to Aguadilla is narrow and runs downhill through farmland. By the time we were halfway down the hill, we’d missed two head-on collisions by inches. I hadn’t fully realised before, but our driver was seeing-double-drunk. As passing headlights came towards us, he’d drive straight towards them. Since I was sitting on Jimmy’s knees on the left-side of the back seat with no seatbelt on and my head wedged against the roof, the coming collision was going to be infinitely worse than a rusty knife in the eye.

By the time we reached the bottom of the hill, we were doing about a hundred clics and I could see in slow motion what was going to happen next. Our road met the main road at such an angle that there would no need for our homicidal driver to slow down to join it. In the distance, a single car was heading towards us at the perfect speed to meet us head-on where the two roads joined. Sure enough, our driver ignored both stop signs and drove straight at the onrushing headlights. Marco, in the passenger seat, grabbed the steering wheel and pulled it to the right. By the grace of God, the driver of the other car did the same thing and at a closing speed of a couple of hundred kilometres an hour, we passed within a few centimetres of each other.

As soon as we’d stopped fish-tailing and regained coherent motion, I had to find a way to escape. Knowing that even a drunk can picture the consequences of someone spewing in their car, I announced I was about to throw up. My band-mates weren’t having any of it: “No, no, you’ve gotta come, man. You’re the only one who knows the words to the songs” and we continued weaving at high speed towards Aguadilla. With desperation approaching panic, I was surprised to discover that while my nausea had begun as a lie, I could now easily produce real vomit if required. But before that happened, the driver got the picture – he was probably renting the nice BMW I was trapped in – and he pulled over and stopped.

I climbed out and fake-stumbled to the roadside fence, pretending to be about to yak. Marco followed me over to see if I was okay. I’m fine, I said, but I’m not getting back in that car. Okay, said Marco, I’ll keep you company. So we grabbed our guitars out of the trunk, waved the others off to Aguadilla and walked the three kays back up the hill to Puntas. Whenever headlights appeared, we hid behind trees, giggling as if we were ten year olds playing ‘Spotto’, to avoid the attention of the night’s other drunk drivers.

Like the Wild West, it seemed there were no police in our corner of Puerto Rico. This was why most homes were completed by the addition of at least one brute of a dog who’d rip your leg off given half a chance. This I discovered the only time I walked the few kays home at midnight from the boys’ valley farmhouse. As I tip-toed past each one-acre property, a different breed of hellhound came crashing through the darkness to bark, snarl and salivate in my direction. All that stood between me and live disembowelment were flimsy wooden posts connected with just enough rows of barbed wire to keep the beasts on their home turf. The big stick and half-brick I’d picked up for defence would have been as good as useless if one of the dogs had broken through. The only effect these make-shift weapons had was to alarm the town drunk who witnessed me emerge from the darkness at the edge of town after I’d run the gauntlet.

Another American our gang knew had rented a house near Puntas for the six month surf season. He was living what he thought would be the dream: surfing every day it was good while growing a forest of hydroponic marijuana in his attic. He planned to sell this crop locally, or send it back to the states somehow, to pay for his next surf adventure or three. Intelligent and talented, he didn’t seem like the guy who’d choose that path. He told me this had been the worst six months of his life. As soon as the plants had started growing, he’d become paralysed by paranoia. He couldn’t share his secret with anyone, even his closest friends, in case their gossip found its way to the wrong ears. It wasn’t so much the police he feared. Much more dangerous were the invisible Puerto Rican criminals who had their own drug-growing operations and would tolerate no gringo competing with their trade.

The last time I saw my mate, let’s call him Billy, after the young drug-smuggler who ends up in the Turkish jail in ‘Midnight Express’, was at L’Estacion Bakery in Rincon one Wednesday at lunchtime after a morning of good surf. I’d watched Billy park his car in the ninety degree spaces across from the bakery. As he crossed the narrow two lane street, his truck silently followed him, rolling backwards down the gentle slope of the carpark, then curving sideways on its previous lock across two lanes of traffic. Billy must have left it out of gear and forgotten to pull the handbrake on. He was lucky it didn’t run him over. Instead, it swung gracefully past several slowing cars, somehow missing everyone and everything, until it came to rest against the curb. It wasn’t until I met Billy at the bakery door to point it out, that he saw what had happened. Over lunch that day, he told me he’d decided to get the hell out of Puerto Rico and disappear back to America. He’d leave the now fully grown crop in the attic for the landlord or the next tenant or someone, anyone, to deal with. The day before, we’d all heard the too-believable rumour that an American in a village just up the coast had been shot in the head by a Puerto Rican gangster for reasons that were too easy to guess.

The only time I saw police of any sort in Puntas / Rincon was on my first morning at Domes Beach. I’d got up before dawn and walked through the fire-fly-filled bush that separated my place from the sea. As I arrived by the decaying dome of the decommissioned nuclear reactor that gives the beach its name, I heard shouting and running. A hundred metres away, three rough young men were doing their best to disappear up the hill into the low trees and scrub. Pursuing them were half a dozen men wearing dark blue uniforms saying ‘Immigration’. By the time I’d checked the surf, two of the young men had been caught, handcuffed and man-handled into a van; the other might have got away. I learned later this corner of the island is a popular spot for illegal immigrants arriving by sea from the Dominican Republic, just fifty kilometres to the west across the Mona Channel. Since Puerto Rico is an American territory, illegal immigrants from the Caribbean try to use it as a stepping stone. If they can get to PR, it’s easier to sneak into the USA by some backdoor than it is from their home islands.

There were other manifestations of Puerto Rico’s relationship with the USA. My first hour in PR was spent in an ageing taxi trapped in a traffic jam on a twelve-lane highway in the capital city, San Juan. With zero public transport on offer, the only way to travel the hundred and fifty kays to the surf coast was via the most expensive taxi ride of my life. Luckily I shared the fare with a young kid who introduced himself as Danny from Brooklyn, New York. Danny told me he was making the journey to Rincon to, quote, ‘make something of my life’. Since he wasn’t a surfer, it’d be a fair guess to suspect he was beginning a career as a drug mule.

Another enduring monument to the USA’s relationship with Puerto Rico was the – to give it its full name – Boiling Nuclear Superheater Reactor that the US government had built and operated through the 1960s a hundred metres from the island’s best surf. This location had been chosen because the fallout from any catastrophe would be carried by the prevailing winds across the Caribbean Islands, Central America or Europe, instead of the USA. God bless America. The eerie, rusting dome of the decommissioned reactor loomed forever above the otherwise rural coast. It wasn’t surprising that on a concrete wall not far from the reactor, someone had spray-painted ‘OUT OF PUERTO RICO, GRINGOS CABRONES’. Cabrones is Spanish for arseholes. It wasn’t hard to see the artist’s point.

The local I got to know best was my landlord, Tony. He’d created a unique living space by painting the floor, walls and ceiling of my single-room apartment in an exuberant melange of red, white and blue. It was the perfect digs for me: enough of an ocean view for surf-checks; just a five-minute walk through the bush to the waves; and best of all, only fifteen bucks a night.

Tony had his demons, and one of them was a child’s baby-doll that hung by its neck from a length of wire nailed to the eave of his house so it was visible from the street. Tony grew very upset when I asked him why it was there. His English was only a little better than my Spanish, which I had just embarked on learning, but as far as I could understand, there had been some massive disagreement with someone in his family and he’d woken one morning to find the ghoulish baby-doll hanging there. It was Puerto Rican voodoo, an evil curse, he explained, and there was nothing he could do about it.

Tony blamed the curse for driving him to drink. Each time we talked during our four weeks as neighbours our conversation veered back towards the doll. I wanted to help him with it and hoped that my status as an outsider might prove useful. Like most Puerto Ricans, Tony was Catholic, so I deployed the theological lessons that had been hammered into us three times a week at school: Hadn’t God defeated Satan and thrown him into Hell? Hadn’t Jesus promised forgiveness? Surely then, ‘good magic’ must be stronger than ‘bad magic’? I don’t know whether Puerto Rican voodoo defers to Christianity, but on the second last morning of my stay, I saw the hanging baby-doll had disappeared.

Apart from my chats with Tony, and the occasional moment in the surf on weekends, I spent nearly no time with Puerto Rican males. It was as if they had given this corner of their island to the gringos, except for when the surf got epic. On the other hand, like the salsa music that strutted and bounced from every house, shop and bus, the Puerto Rican females were around us all day and into the night. I’d played a small part in a school production of West Side Story, and from that had developed the notion that Puerto Rican girls were sexy and sassy. Well, they certainly were. They were there on the beach, in the shops and bars, always smiling and introducing themselves. As far as I could tell, they weren’t prostitutes, and to my knowledge they never permitted direct intimacy. But by gum they could flirt. They reasoned, and with justification, it must be said, that their feminine charm could be their way, and perhaps their whole family’s way, to a more affluent part of the world. I learned early on not to be surprised or offended when the attractive girl who’d been so chatty to me the night before was even more chatty to the gringo who arrived at the beach the next day in an expensive hire car. They were beautiful, engaging and pragmatic. One or two of them brought young children, presumably theirs, when they made day-time visits to Rincon from Mayaguez, the city thirty kays to the south. Their relationship status was unknown, but it wouldn’t have been at all surprising if a father, husband, brother or boyfriend had turned up with a gun or a knife.

So due to the perennial party culture and the flirting of the local girls, it was also no surprise that when a good swell finally arrived after a week’s wait, my eye wasn’t on the ball. Remember: in those days, surf forecasting was your own responsibility and required access to meteorological information beyond my reach in Puntas. Wiping the sleep from my eyes at 10.30 after one beer and pool game too many the night before, I saw dark blue lines wrapping into the coast. Dagnabit! I grabbed my board and some breakfast and ran down to the coast. After jumping off the rocks at El Faro I ended up at Dogmans, about two kilometres south, surfing Indicators, The Point and Marias on the way. The waves were big, blue and powerful, sweeping southwards down our corner of the coast. The names of the waves were just sections of the same almost unbroken reef that stretched for five kilometres and beyond.

Being Good Friday, it was crowded, and for once the local boys were out in force. They surfed aggressively and well and, while we got some waves, us gringos were put firmly in our place. I shared my usually solitary lunch-spot under the trees at Domes Beach with a huge local holiday crowd while whales breached in the Desecheo Channel. The next day I surfed some of the biggest waves I caught that year at Dogmans. The waves weren’t quite as good as Soup Bowl or Cane Garden Bay but I got one of the waves of my life at Domes the next day when I rode a pretty big wave the length of the beach, about three hundred metres. Apparently this was a big achievement.

Rachel and Valerie, two American girls, had set up in the village for the winter, financing their extended stay by taking and selling good photos of the visiting surfers. Once a month they held a slide show at ‘Tamboo Beside the Pointe’, one of the local bars. The surfing community convened to review the month’s best rides and wipeouts. The atmosphere rivalled my first surf movie experience in 1975 when Hal Jepsen’s ‘Super Session’ was shown at the Balgowlah Cinema in Sydney. It was interesting to discover that a still image shown on a big screen in a crowded, dark room can elicit the same response as a moving image. The audience’s subjective guesses about what happened before and after that single captured millisecond create an unresolved tension with its own unique, unspoken drama. There’s also time to study every detail of that moment in much more depth than when watching a real-time moving image that rolls directly on to the next milli-second, then the next. Andrew Kidman and George Greenough, among others, have employed this principle in their seminal films by showing waves and rides in super-slow motion, almost frame by frame.

In the last few days on Puerto Rico, I realised I was asking too much of my beloved surfboard, Byron, to make the journey on her own. Water had been getting in through cracks in the fibreglass around her nose, and dents were deepening where the foam was starting to collapse. I asked the local boardmaker, Rusty Ellwood, to make Byron a companion: a modern six foot ten thruster with plenty of volume, wrapped in carbon fibre cloth for added strength. Then I bought a properly padded double-board-bag to replace the feeble bubble-wrap sleeve that Byron had braved all her life.

April was half-gone. It was time to leave the Caribbean islands and jump two thousand kilometres west to Central America.

Vamonos a Costa Rica!

Chapter Five

Before (and a bit after) 1993

Looking back, it seems pretty clear I was born with a strong case of the wanders. Was it a blessing or a curse?

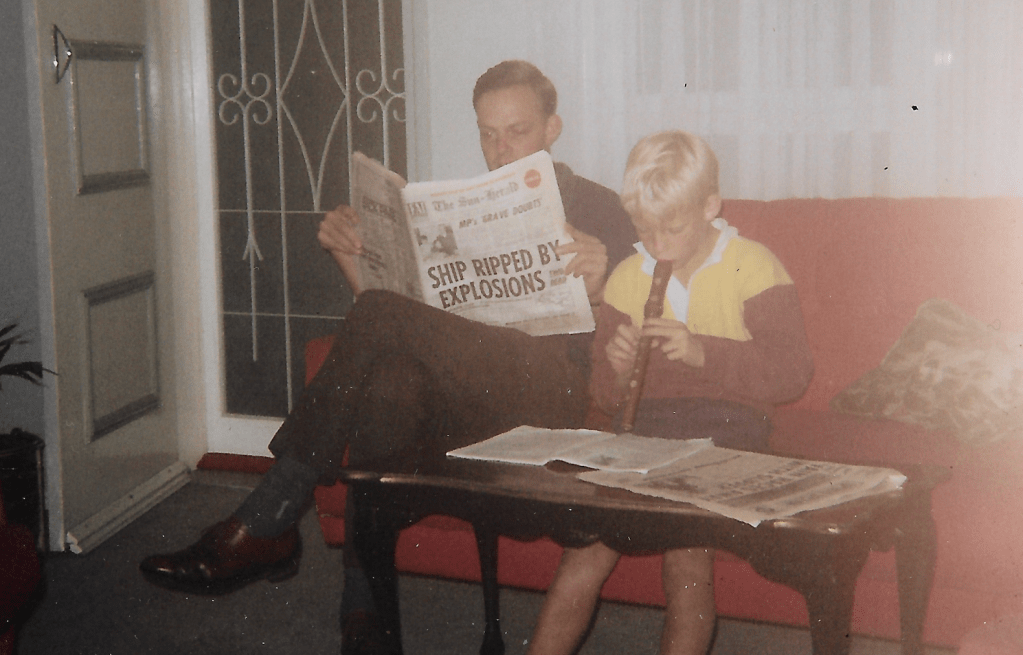

As soon as I could walk, I went adventuring. At a few months less than two years old, I escaped from my mother and tottered into the road to head-butt a fast-moving car. The bright light of the hospital’s x-ray room is one of my earliest memories. Alive by the skin of my teeth, I pursued an obsession with the railway lines that disappeared into a tunnel near Clifton Downs station. I liked the trains too, but it was the tracks’ harmonic curve and disappearance into a black hole in the hill that held me in thrall. Not long after, my trainer-wheeled bike took me wobbling round the paths and gothic quadrangles of Clifton College where Dad taught in Bristol. Then my parents bought a caravan and in summer time we followed Dad’s cricket games for Dorset round southwest England. In my first five years we had five homes, including my grandparents’ in London and Witney, and I discovered that nothing beat the thrill of waking in a different bed, in a different place.

We emigrated to Australia when I was six. The flight was long and terrifying. Our first stop at Zurich was aborted due to a severe blizzard. We were forced to fly on to Beirut where we were struck by lightning as we landed. It would be ten years before I dared get back inside a plane again. Once safely settled in Sydney, my modes of exploration moved to the harbourside bushland, stormwater drains, naval bases and railways tunnels of Waverton. By the age of seven I’d been brought home by the police more than once.

At nine we moved to Chatswood, where the three tree-ed acres of Muston Park was our front yard, and Scotts Creek could be followed, through bamboo, factories, toxic mud and concrete spillways, as far as Castle Cove or Willoughby. Fishing rods, skateboards, bikes and billycarts were our evolving passports to adventure. A Sunday morning newspaper delivery round introduced me to the silent, dew-soaked solitude of the predawn world. It also gave me financial independence to explore other dimensions such as Led Zeppelin albums and weapons-grade fireworks, purchased each June from the newsagent, ever happy to encourage pyrotechnically minded pre-teens. With these, we’d set the park aflame, blow up model planes, glass bottles, and somehow not quite our fingers and faces. The excitement was heightened by the addition of a stray, manic kelpie that adopted me for a couple of years, until he mistimed his thousandth attempt to round up a speeding semi-trailer in four lanes of traffic and was run over. I cried for a month.

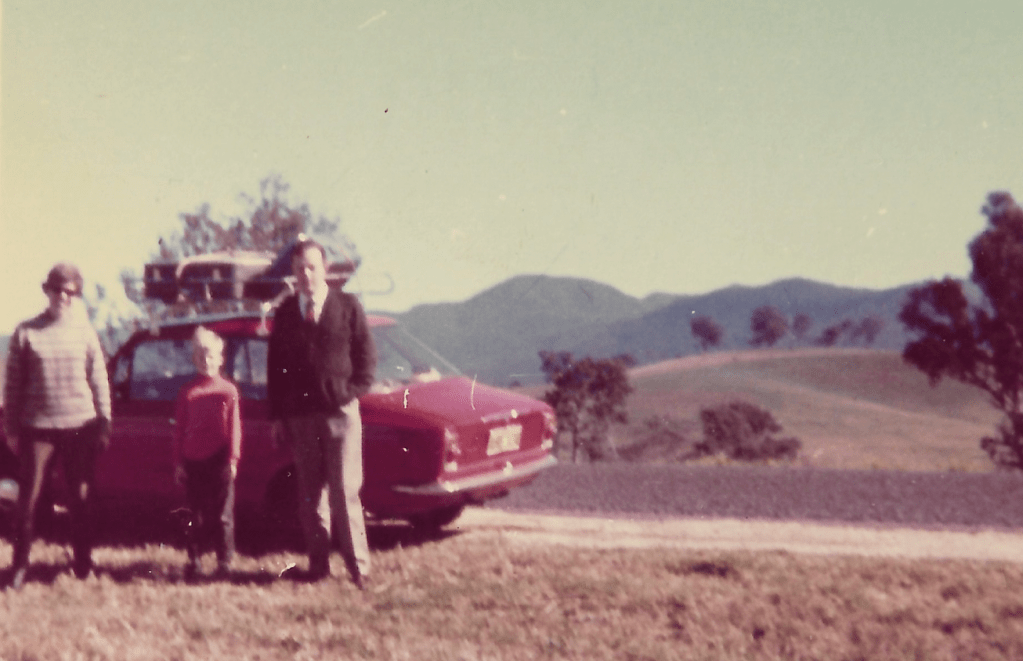

In the school holidays, Mum led us on random expeditions round New South Wales. Once we drove northwest towards Bourke, joining in Mum’s quest to (quote) “drive until we get to nothing”. Sadly we were forced to turn back unrewarded when our tiny red Corolla’s windscreen was shattered to a million pieces.

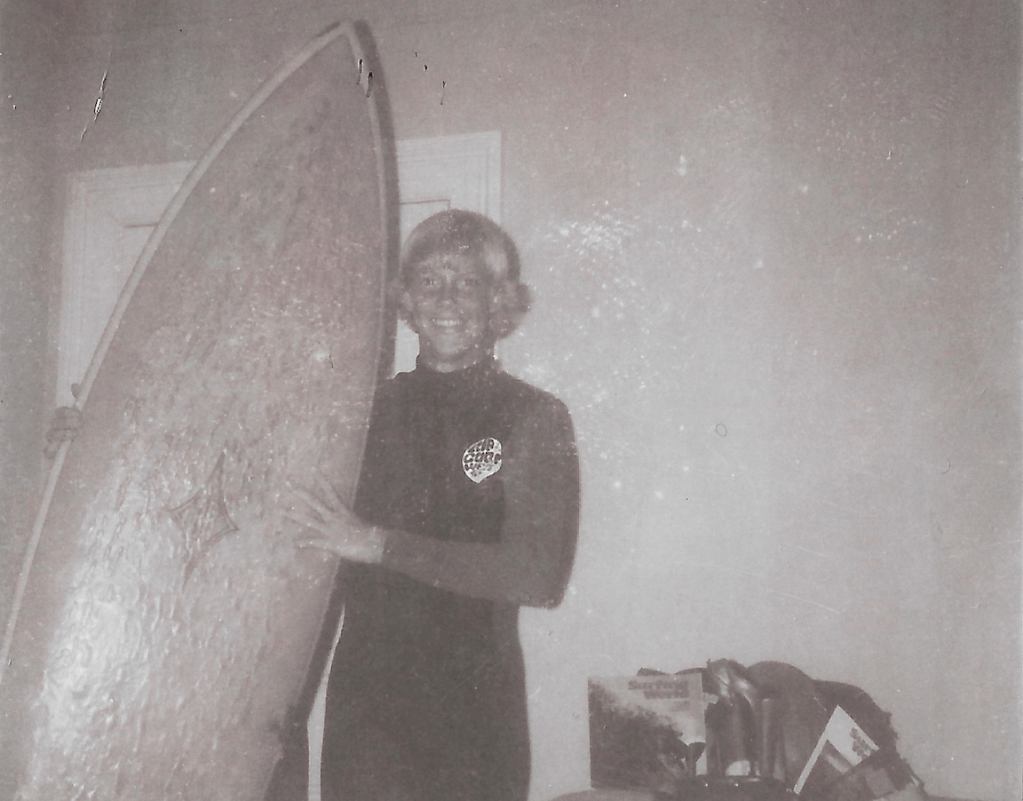

At thirteen we moved back to North Sydney and I fell in love with surfing via skateboarding and the epically romantic surfing magazines of the mid-1970s. Every issue featured electrifying stories and images of surfers travelling in ones and twos to ride undiscovered waves on the exotic coasts of every ocean. Dreaming of one day making my own leap into the unknown, most Sundays I’d get up at five to trek with my second-hand surfboard through the deserted office buildings to catch the snail-paced buses to Manly or Bungan.

My Year 11 maths tutor couldn’t help me with quadratic equations, but his Friday night slide shows gave another crystal clear vision of how spectacular life could be. Andi and his fellow mountain-climbing super heroes disguised as mild-mannered Clark Kents spent their uni holidays climbing progressively more challenging Himalayan peaks: first Changabang and eventually Everest, with no sherpas or oxygen, where Andi’s crampon broke fifty metres from the summit, leading to the loss of all his fingers on the descent. Not that it’s ever a competition, but the adventures that happened to me in subsequent years were tame compared to what these blokes experienced.

At uni my mates and I got cars and over the next few years explored Australia’s southeast coast from Noosa to Port Campbell. We slept in tents, musty caravans, Honda Civics and Kingswood station wagons. I discovered how much I loved living rough on a shoestring budget.

Another world opened up when I got a dogsbody job in a recording studio where Midnight Oil, INXS, Cold Chisel, Duran Duran and so many other great bands of the early eighties rehearsed for their Australian tours. Some friends and I made our own band and we did well enough playing in the pubs around Sydney to add two years to my ramshackle three year Arts degree.

Then, out of the blue and by accident, I became a schoolteacher. I’d only called the school to enquire about the job to convince my parents I was serious about finding paid work. I had no teaching qualification, just my simple B.A., but to my surprise the Headmaster called me in for an interview, then gave me the job. Just three days later I taught the causes of the French Revolution to my first History class, and by recess I’d realised teaching was the best job in the world. The longest and most complex adventure of my life had begun.

Three years later it suddenly struck me I had enough money to leave and not come back. What was I waiting for? I bought a one-way ticket to London and sold everything I owned. For fourteen years I taught in England, Ireland, New Zealand, Canada and Indonesia. In the holidays and long breaks between jobs, I hitched, bussed and trained through Western Europe, Turkey, Africa, Asia and the Americas.

1993’s year-long journey home to Sydney through the Caribbean and Latin America was somewhere near the midpoint of this time of my life.

These nomadic years were as full an experience as this little black duck could ever have imagined. Every minute on the road was an education no school or university could give. Not knowing where you’d sleep that night or what you’d find for the next meal heightened your senses and thinking. You could meet anyone or no-one; end up at your imagined destination or somewhere utterly different. Where your wits intersected with the winds of fate, you appreciated every bit of luck and learned to cop the hard times on the chin.

I wondered what could ever make me want to stop.

Chapter Six

Costa Rica

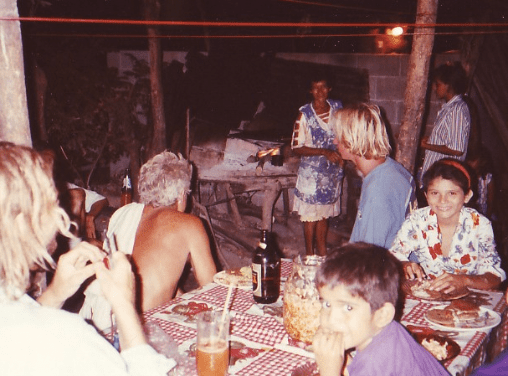

After the funky jazz of Puerto Rico, Costa Rica was a good old-fashioned, country-soul surf mission. For twelve days, Joy and I searched for waves along the thousand kilometres of Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. We forded rivers, survived storms and slept mostly in the sweaty, lain-down front seats of our hire car.

When we’d parted in Barbados two months before, Joy had asked me to call her at her mum’s place on the US east coast sometime in early April. If Joy’s work at the hotel in Hawai’i was still on-hold due to hurricane damage, she’d been keen to join me on another surf-trip. So when I called from Puerto Rico and said I was heading to Costa Rica, Joy booked a flight to meet me two weeks later in San Jose airport at 7pm. All it took to confirm our arrangements was one more three-minute phone call a few days later: no flurry of texts, facetimes and emails required. Easy beans.

My flight arrived in San Jose an hour before Joy’s, so I passed the time by searching for a rental car. Every company with a counter at the airport told me their cars were either booked out or astronomically expensive. Amazingly, when I went back to the same counters accompanied by Joy an hour or so later, we found just the car we wanted at a very reasonable price. I wonder why.

By the time we’d done the paperwork and loaded our stuff into and onto on the car, it was too late to get any value out of paying for a hotel. So we began our adventure with the time-honoured tradition of an all-night drive to the coast. Finding the right highway to take us from the airport out of town was a trial. But once on track, it was a pretty straightforward three-hundred-kilometre, five-hour drive to our first destination: the waves at Witches Rock in Costa Rica’s far north. This isolated spot had become a favourite of the American surf magazines in the few years prior. The perfectly formed, cobalt-blue waves breaking on a white-gold beach in a pristine national park were made even more photogenic by the grey-white rock-stack that towered above the horizon half a kilometre out to sea. It was a surf-photographer’s dream.

While the empty, well-built highway made night-driving straightforward, staying awake proved more difficult, so a couple of times we pulled off the road to catch a half-hour’s sleep. Parked in the middle of nowhere in a hire-car full of gringo stuff and surfboards stacked high on the roof, we felt like an invitation to robbery, or worse. Our first lay-by was a narrow shoulder of the highway lit up by the bright orange lights of an oil refining plant. We weren’t sure if the lights made us more secure or more of a target, but we dodged that bullet and in the early dawn light we found the rough dirt track through the Santa Rosa National Park to the Witches Rock beach.

It was the first time I’d been beside the Pacific Ocean since I’d left Sydney six and a half years before. And this morning it was indeed pacific: no waves, no wind, just deep blue, like a lake, all the way to the wide horizon. But in the distance to the north, we could see the famous offshore monolith that gives the wave its name. So we packed the only food we’d brought – one small muesli bar each and a bottle of water – and went for a stroll down the long, empty beach.

We’d gone a couple of kilometres before we realised the mistakes we’d made: the carpark was in a corner of the beach protected from the swell; and the beach was longer, the rock was taller, than had appeared at our first dawn glance. As we walked, tiny lines of open-ocean swell grew from ripples to ankle-slappers and beyond. By the time we neared Witches Rock, the swell-lines were head-high and the waves were absolutely firing. Joy decided she was too tired to do anything more than catch up with some sleep on the beach, so in the rapidly climbing heat I jogged back alone to the car to get my board. By the time I’d completed the four kay round journey I was fully cooked, but I managed a few good rides before dehydration, hunger and exhaustion set in. The waves were every bit as good as the magazine photos had promised: hollow, fast and, for a beach-break, long.

At late morning we trekked back to the car, desperate for food and water. With none of either available in the national park, we made the hour-long drive on dirt tracks back to the nearest town. We’d planned to return to Witches Rock to camp and surf the next day, but by the time we’d found lunch and rested up, the decision was made to continue driving south in search of other waves, both known and unknown.

First up was Tamarindo, a well-advertised surf-town about two and a half hours’ drive away. Contrary to our Witches Rock experience, Tamarindo didn’t live up to its hype. Sure, we only gave them a couple of days to show their wares, but the quality of the waves seemed exaggerated. Even more decisively, the town was expensive and commercialised, with new tourist developments and quite a few older ex-pat Americans giving it the feel of a new suburb of Florida or Southern California. This wasn’t what we were travelling to experience, so after a couple of days we a drove a hundred kilometres further south towards Samara on the Nicoya Peninsula, to find places without postcards.

Someone somewhere had told us to look out for a beach called Camaronal, but it wasn’t mentioned on our undetailed map, and road signposts of any sort were few and far between. A good surfbreak only needs a couple of hundred metres of sand or reef to do its thing, so searching a patchily accessible one hundred kilometre stretch of coast with too little information is a helluva challenge. But the dreamed-of reward of finding and riding, ideally alone, an elusive wave in an exotic locale, makes this search forever enticing.

After Samara village, the decent road we’d been following turned directly inland, and the road that we guessed would stick closest to the coast grew rough. After following a series of frustrating, waveless dead ends around the little village of Puerto Carrillo, the track that seemed to carry the most promise simply disappeared into the River Ora. It seemed there might be a rough track about fifty metres away on the opposite riverbank, but wouldn’t some sort of punt be needed to get us across? Over a late lunch by the river, we debated our options. I was in the process of getting organised to wade and/or swim across the river to assess its depth when we heard an unseen truck approaching down the rough hills on the far shore. As the truck emerged from the scrubby country, it shifted down through its gears and followed the track gingerly into the river. It lurched around a fair bit as it bumped over big rocks on the riverbed, but the gently flowing water was less deep than we feared and the riverbed was plainly firm enough to take the truck’s weight. Okay then. Our four wheel drive rent-a-car didn’t ride as high as the truck, but it was clear we had too good a chance of making it to chicken out. We took the plunge.

After a couple of adrenalised moments when it seemed we might have wedged our wheels between rocks, we cleared the river and were rewarded with the roughest track and steepest hills we’d encountered. Adding to our growing anxiety about getting stranded in the middle of nowhere, a massive electrical storm blew in from the sea. Driving rain made it nearly impossible to see through the windscreen and several times it seemed we were trapped in deep divots in the red-mud road. While lightning and thunder seemed to aim personalised attacks on our lonely souls, we clawed up, then down, the winding spine of a series of low hills. Eventually, in the last light of day, we returned to flat land at sea level. As the countryside grew less wild, Joy thought she saw a handpainted sign saying what might have been ‘Camaronal’ illuminated by a lightning flash. But neither of us were in the mood to explore further. Instead we searched for a safe, quiet place to park up, have a bite to eat from the food we’d packed, and sleep. This haven we found a few kilometres further east at a lonely beach village called Playa Islita. Despite the last of the storm crashing around us, we fell asleep pretty quickly in the front seats of the car while little wind-born waves washed against the high-tide line.